A Brief Introduction to Machine Learning

This article was originally posted on LinkedIn on 8/11/2017

Machine learning is a hot topic recently, with big names like Google and Facebook making news with extremely sophisticated algorithms that sometimes sound like science fiction. The truth is that machine learning is an extremely useful and practical set of techniques which almost definitely has concrete applications in your business, whatever the size or industry.

What is Machine Learning?

A commonly-accepted definition of machine learning is that given by computer scientist Arthur Samuel in 1959:

A field of study that gives computers the ability to learn without being explicitly programmed.

That’s a conceptually simple answer, but concretely, what is the process of “machine learning”? What’s the output? And how can it be applied to your data? I’ll endeavor to answer all of those questions over the course of a few articles, but first, I’ll propose the following, more concrete definition.

Machine learning is the process of using data to automatically build a model, which takes as input some set of known features and gives as output some prediction. Let’s define some terms.

Some Terminology

The Model

The output of a machine learning technique is a model. Models take various forms and different type of models are applicable to different classes of problems, but in general a model is a mathematical function which takes some set of inputs and produces a prediction of some quantity that’s not readily available for measurement. Here are a few example of models:

- An equation that takes as input various properties of a loan applicant (e.g. income, outstanding debt, requested amount, etc.) and gives as an output the confidence that the lender will default on a loan.

- An equation that takes as input the color values of pixels of a photograph and gives as output an identification of the object contained in the photograph.

- An equation that takes as input the current state of a Go board and gives as output the move that gives the best chance of winning the game.

Obviously, these equations all look very different, and we’ll discuss some of the different types of machine learning models in a future post. Machine learning is the process of using the data to automatically build the model.

Features

Features are the input to a machine-learned model – they’re any piece of information that may be useful for prediction. In the example above of predicting loan defaults, income, outstanding debt, requested amount are all features. There may be many other features that could be useful, and some of them may be combinations of other features; for example, income-to-debt ratio, or credit score (which is of course the output of a different model including many of these same features).

Overfitting

Overfitting is fitting your model to random noise in the data. It’s usually the result of having an overly-complex model; for example, having too many input parameters relative to the number of observations. There are several techniques to avoid overfitting; a couple of common examples are cross-validation, where the quality of fit of a model is assessed on a separate set of data from the one it was trained on, and regularization, in which an additional penalization term is included to give preference to models that use fewer parameters.

Classification of Machine Learning Problems

There are three major classifications of machine learning tasks:

- Supervised learning: The model is constructed using a known set of “training data”, which includes all of the features as well as known values (“labels”) of the output we’re trying to model. The goal of supervised learning techniques is to arrive at a model that maps the input features to the labels.

- Unsupervised learning: The learning algorithm isn’t given labels; the goal is to discover unknown structure such as clutsters or other patterns.

- Reinforcement learning: The algorithm is given rewards and punishments based on it’s success at achieving a certain goal – for example, a Go algorithm would be rewarded for changes to a model that increase the proportion of the time the model wins and punished for changes that decrease it. The algorithm aims to maximize rewards and minimize punishments.

Tasks can also be classified by the desired output of the learned model. Three of the most common are:

- Classification: Data are divided into two or more classes or “labels” (for example, “hotdog” vs. “not hotdog), and the goal of the learning task is to produce a model which assigns inputs to one or more of these labels.

- Regression: The output is a continuous number (e.g. price of a given commodity, production of a proven oil well) instead of a discrete classification, and the model provides and estimation of the target output.

- Clustering: An unsupervised analog to classification; inputs are to be divided into groups, but the groups aren’t known before the model is constructed.

Example Application: Predicting Home Prices

Here I’ll present a very simple example using a technique you may be familiar with: linear regression.

Consider the HOUSES dataset, which contains data about real estate listings in San Luis Obispo County, California. Let’s use machine learning to build a model for home price using these data.

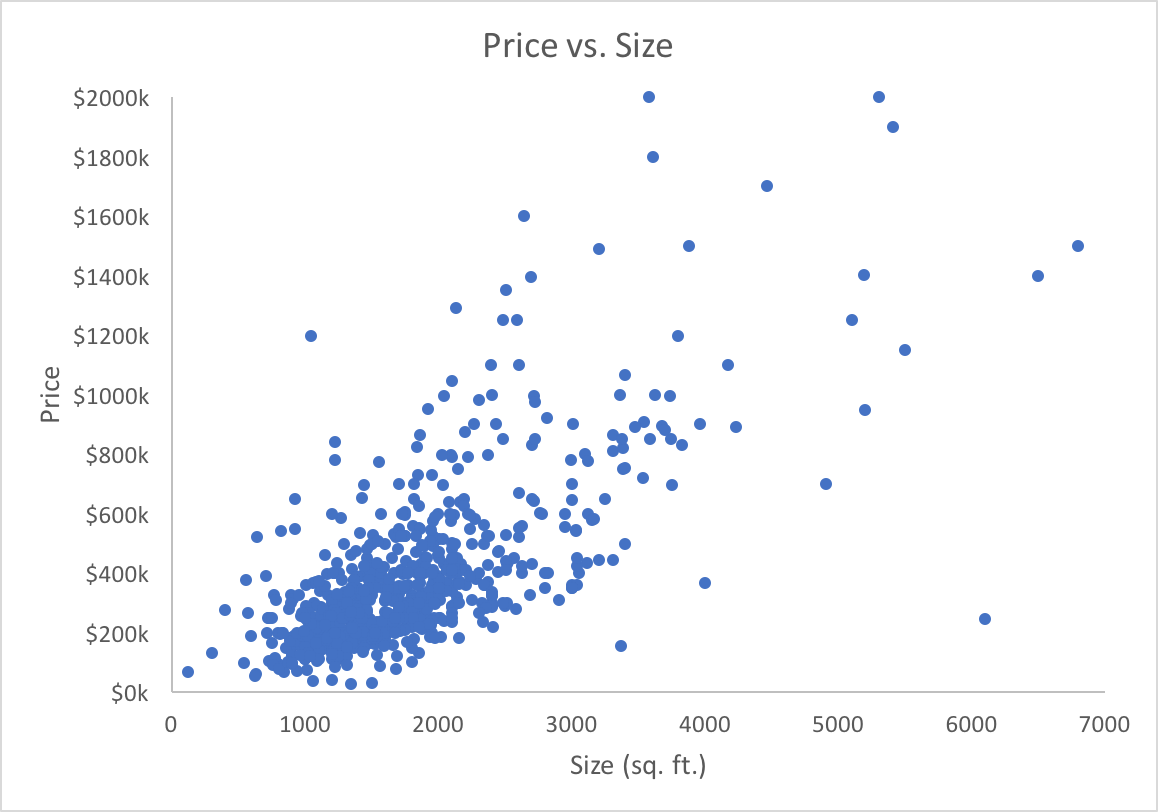

Below I’ve plotted home price vs. size (in square feet). This seems like a reasonable comparison; you’d expect, on the whole, larger houses to have higher prices, and we can see that’s true.

Note that I’ve excluded some data points from the plot for clarity; they’re included when fitting the model.

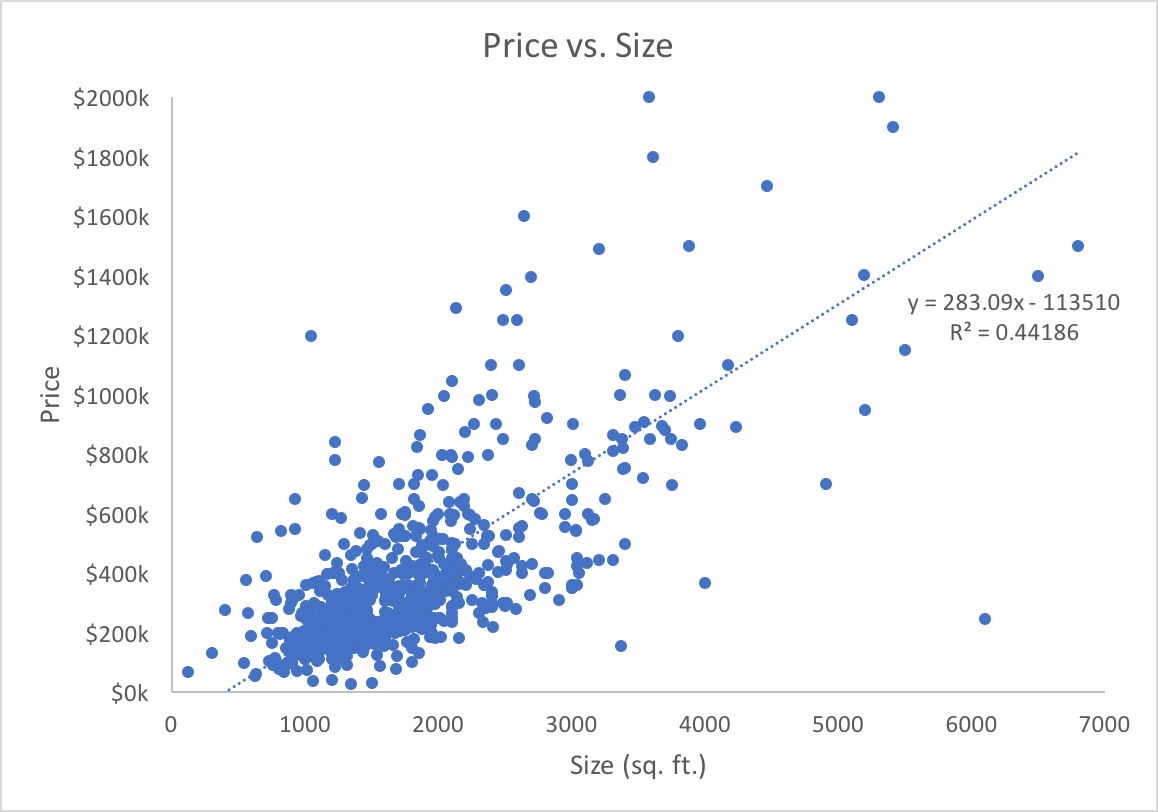

There are some other variables in the dataset that may be useful for building the model, but for now, I’ll use just size, and I’ll use the convenient “Regression” functionality built into Microsoft Excel charts. Linear regression uses statistics to determine the parameters (slope and intercept) of the line which best fits a set of data; it’s constructing a model (the linear formula) using one feature (the size of the home in square feet). You can see the result below.

As you can see, the machine-learned model is

price in dollars = 283.09 * (size in sq. ft.) - 113,510

The regression fit also provides a coefficient of determination, denoted R², of approximately 0.44. R² is a measure of how much of the variability in the independent variable (home price) is accounted for by the model, or conceptually, how good of a model we’ve built. It ranges from 0 (for a model with no predictive power) to 1 (for a model that perfectly matches the data).

Of course, machine learning techniques in practice can produce much more complex models, using large numbers of features and learning very subtle relationships. I’ll describe examples of such techniques (and how to evaluate them) in a future article.

How does this relate to AI?

Machine learning is a sub-field of artificial intelligence (AI). AI is a general term for computer systems that can perform tasks that normally require a human to perform, such as image recognition or decision-making.

AI systems can be machine-learned, but they need not be. Imagine two chess-playing AI systems. System A was created by interviewing Grandmasters extensively and encoding a complex set of rules that mimics their decision-making process. System B was created by training a model on a large corpus of past chess matches, optimizing for the decision that most often increased the chance of victory in those past matches.

Both systems are AI systems for playing chess, but only System B involves machine learning.

What’s this “deep learning” I keep hearing about?

Deep learning is a particular type of learning; it involves the use of artificial neural networks with multiple “hidden layers”. The technical detail of such techniques is far beyond this blog post; however, suffice it to say that deep learning is a technique which can result in extremely powerful models given large computation time, a large amount of input data, and comfort with a model that can not be interpreted intuitively.

Conclusion

This has been a brief overview of what machine learning is; in my next article, I’ll describe what using machine learning to build a model actually entails.